The World Health Organization (WHO) announced the discovery of a new coronavirus in two patients who died from a mysterious, rapidly-fatal disease in the Middle East on 23 September 2012. Shortly after, we received many phone calls from concerned relatives, friends, and reporters who wanted to know whether severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) had returned.

This was no surprise to us as clinical microbiologists working in Hong Kong, where SARS coronavirus was first identified just a decade ago. During the SARS epidemic in 2002-2003, one of the worst epidemics in our city’s history, 1,755 people were infected and 299 died from the dreadful infection.

It later became clear that Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus is a related but different coronavirus from SARS coronavirus. MERS-CoV is actually more closely related to bat coronaviruses we found in Hong Kong some years ago. However, many people in Hong Kong and other parts of Asia still call MERS the “new SARS”, and with good reason for doing so.

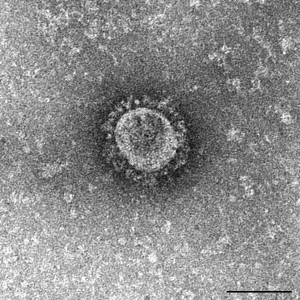

Both illnesses are caused by a family of viruses called coronaviruses – a name given to them for their “crown-like” (corona) appearance under the electron microscope. They both cause severe respiratory diseases associated with systemic symptoms such as fever, muscle pain, and diarrhea. And they are both likely to have originated in bats, and then adapted to other mammals (dromedary camels in the case of MERS coronavirus and civet in the case of SARS coronavirus) before infecting humans.

Apparently, MERS has an even higher death rate (>35%) than SARS (~10%). Fortunately, in the past three years, MERS has not been transmitted from person to person as efficiently as SARS was.

Person-to-person transmission of MERS

But the recent large outbreak of MERS in South Korea has heightened the fear that this non-sustained person-to-person transmission of MERS coronavirus might have changed. Within just three weeks, more than 160 people have been infected and over 4,000 close contacts were exposed and quarantined.

Most importantly, there are a higher percentage of “third generation” and even “fourth generation” transmissions – meaning that people who were not in direct contact with the index patient still got infected from contacting the people who got infected from the index patient (“second generation” patients).

This observation raises the possibility that MERS may continue to spread in the community – among people who do not have any contact with health-care facilities. Such a mode of spread brings to mind the early phase of the SARS epidemic, when the infection started to spill over from health-care facilities into the community, eventually resulting in large community outbreaks in Hong Kong.

The official response to the South Korean MERS outbreak

The South Korean officials are under no less pressure than those in Hong Kong and mainland China during the SARS epidemic. They have been similarly criticized for 1) being slow in response, 2) lacking openness to the public, and 3) failing to effectively control the spread of the outbreak.

It was indeed surprising that the index patient had to visit four hospitals before the diagnosis of MERS was established. This delay in diagnosis likely contributed to the spread of MERS to so many different people.

After the index patient and the initial secondary cases were confirmed, the government decided not to release the names of the hospitals because “it might raise unnecessary fear”. It soon became apparent that this was doing the exact opposite – people were more afraid when clear and complete information was not being told.

Suboptimal compliance to basic infection control measures that are essential for preventing the spread of a respiratory tract infection – things like wearing masks, gloves, and gowns – was reported among health-care workers and visitors in some of the affected health-care facilities initially. Furthermore, some exposed contacts who were supposed to be under quarantine were found to be traveling across and out of the country – making contact tracing even more difficult.

Nevertheless, compared to a decade ago, a few major improvements were apparent in the way this MERS outbreak is being handled by the global community, Asia and South Korea. First,there is much better and quicker international collaborative response – the WHO sent a team of experts with experience in handling the MERS epidemic in the Middle East to South Korea last week. Better communications among the health authorities of South Korea and other regions have facilitated the tracing and quarantine of the first imported case of MERS in China – a symptomatic man who travelled to mainland China via Hong Kong from South Korea.

With these measures in place, we remain cautiously optimistic on the development of the MERS outbreak in South Korea.

Second, with the much more powerful molecular techniques available nowadays, complete genome sequences of the latest Korea MERS-CoV isolates were released quickly which showed that the virus has not undergone substantial mutations.

And finally, the South Korean government soon became aware of the importance of transparency. The names and locations of the health-care facilities involved and the number of infected and exposed contacts are being updated on a regular basis (also available at the WHO website: https://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/en/).

With these measures in place, we remain cautiously optimistic on the development of the MERS outbreak in South Korea. Nevertheless, it is perhaps now time to pay more attention to the epicenter of MERS – the Middle East – where continuous animal-to-human transmissions of MERS-CoV are still being regularly reported nearly three years after the first cases were identified. This is unlike SARS which was rapidly terminated after wild animal markets were closed in southern China and human cases were contained.

A lot more coordinated research efforts are needed to better understand MERS-CoV and sort out how we can stop the MERS epidemic from truly turning into another “SARS” or something even worse.

Virology Journal is accepting submissions for a thematic series on coronaviruses, including MERS and SARS, edited by Susanna Lau. For more information, please contact the Editorial Office at virologyjournal@biomedcentral.com.

For more information on MERS, take a look at the following:

1) WHO: https://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/en/

2) Chan JF, Lau SK, To KK, Cheng VC, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015 Apr;28(2):465-522.

3) Al-Tawfiq JA, Zumla A, Memish ZA. Coronaviruses: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in travelers. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014 Oct;27(5):411-7.

4) Raj VS, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA, Haagmans BL. MERS: emergence of a novel human coronavirus. Curr Opin Virol. 2014 Apr;5:58-62.

Susanna Lau & Jasper Chan

Jasper Fuk-Woo Chan is currently a Clinical Assistant Professor at the Department of Microbiology, The University of Hong Kong. His research focuses on emerging respiratory viral infections and opportunistic infections in immunocompromised hosts.

Latest posts by Susanna Lau & Jasper Chan (see all)

- The MERS outbreak: an Asian perspective - 18th June 2015

Comments