Elephants and fascioliasis

Fascioliasis is a global economic problem impacting upon human and domestic animal health, but what about wildlife? Although we are used to considering the impact of Fasciola infections on domestic animals such as sheep, cattle, and horses, it is often very easy to forget their impact on wild ungulates, including deer, buffalo, antelope, and even elephants.

Fascioliasis is a serious problem for elephants throughout Asia with continuous reports from India, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia of considerable morbidity and mortality in domestic and semi wild elephants.

Historically, elephants were held in high esteem in human societies being depicted as gods and later being domesticated and even used in battle. Today, throughout Asia, elephants continue to have particularly high importance in religion and culture but also as beasts of burden. Yet despite their importance we still know relatively little about their diseases and the true impact that such infections can have on elephant populations.

An understanding of the consequence of parasitic infections in wild populations of Asian elephants is even more neglected despite the close interactions that domestic and semi domestic elephants have with their wild counterparts.

Wild elephants are in continual conflict with humans for land. In Sri Lanka the conflict is so intense it is estimated to result in the death of at least one human a week and one elephant every two days. Owing to this continued conflict there has been a dramatic decrease in wild elephant numbers due to a lack of space and an eruption of infectious diseases, including the liver fluke Fasciola jacksoni, the agent of elephant fascioliasis.

Fasciola jacksoni: tackling the tricky taxonomy of a terrible trematode

Prof Jayanthe Rajapakse led a team of veterinarians and parasitologists on a 39 month survey of the health of wild elephants across Sri Lanka from January 2000 to April 2003, collecting faecal samples from living elephants and performing autopsies on wild elephants that had been killed as a result of human activity as well as individuals with a fatal burden of F. jacksoni.

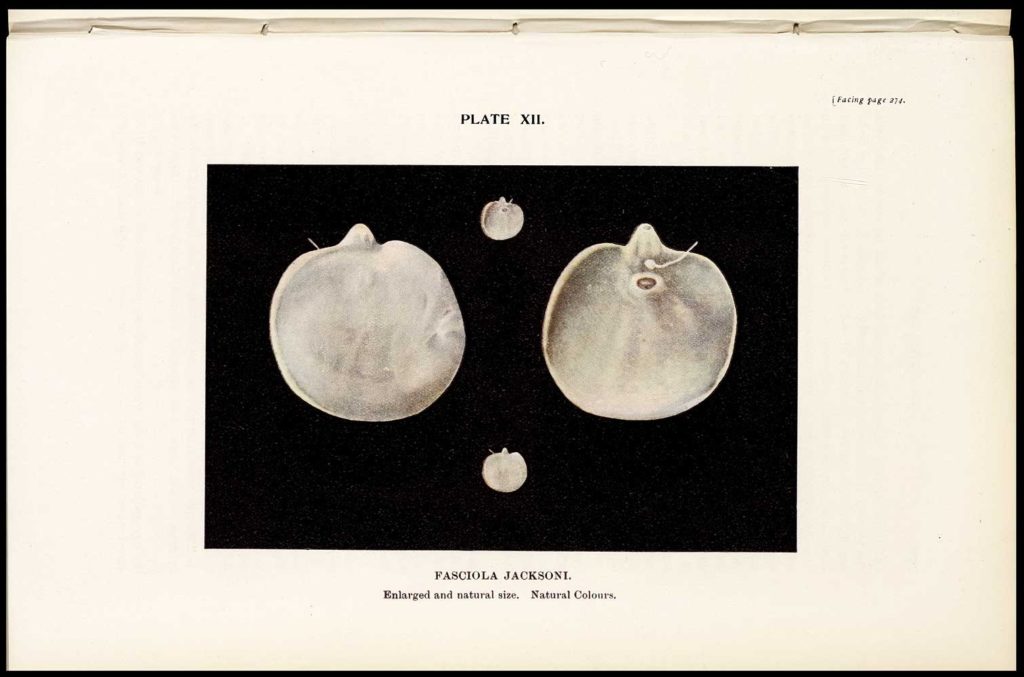

The autopsies showed that over 50% of the elephants were infected with F. jacksoni, with livers showing cholangitis, an inflammation of the bile duct, and major fibrosis of the liver, a scarring of the liver as result of the parasite’s activity. Since then work has focused on improving the identification of F. jacksoni which has traditionally been done on the morphology of the adult worms which can often be erroneous as morphological characteristics of parasites can vary not only at different life stages but also between different hosts.

In 2019, Prof Rajapakse and his team joined forces with Prof T. Hoa Le of the Institute of Biotechnology, Vietnam and me, Dr Scott Lawton, at Kingston University London in the UK, and was able to apply molecular taxonomic techniques to identify F. jacksoni material from wild elephants for the first time (Rajapakse et al., 2019).

Using both the mitochondrial genetic markers cox1, the DNA barcoding gene, and ND1 gene, it was possible to link the genotypes of eggs from faecal samples to adult flukes, but also showed that there was little to no genetic diversity of worms between hosts, indicating transmission between hosts from particular localities. However, phylogenetic analyses of the F. jacksoni showed it to be most closely related to a highly pathogenic liver fluke of deer Fascioloides magna rather than the medically important genus Fasciola, and upon reanalyses of the morphology, F. jacksoni and Fa. magna shared many anatomical traits not seen in members of Fasciola.

Freezing flukes: the ice age and the movement of elephants from Asia to North America

Fascioloides magna is an invasive fluke of deer from North America causing serious damage to livestock especially cattle and sheep in Europe. However, the relationship between the elephant fluke and the deer fluke may be an ancient one.

It has been suggested that the ancestors of the American elephants such as the Columbian mammoth which is a sister species to the Asian elephant, would have taken an F. jacksoni-like liver fluke with them as they migrated across the Bering straights from Asia into North America 1.5 million years ago. Eventually, the parasite would have undergone a host switch into North American cervids and persisted in deer after the extinction of the North American elephants and eventually giving rise to Fa. magna. However, this will need further investigation to really resolve the origins of F. jacksoni and Fa. magna.

A need for further understanding of diseases of elephants and large mammals

The application of molecular tools in the identification of F. jacksoni from Sri Lanka provided crucial tools for the monitoring of fascioliasis, especially as the conflict between humans and elephants continues to intensify. Such approaches are crucial to aid in accurate diagnostics of infection of wild and domestic elephants but also provide tools to estimate transmission patterns.

However, there is a growing global need to monitor diseases of wildlife not only to identify the risk of zoonotic infections that could be potential risks to human and livestock health but also to in order to measure consequence of human impact on populations of wild animals.

Populations of elephants, and other large mammals, are becoming increasingly fragmented into smaller areas, and with this increasing density within limited areas there is also an increase in the risk of infection. This could ultimately lead to natural low-level infections increasing in intensity and becoming a real conservation issue.

Comments