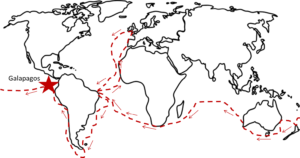

A small archipelago in the Pacific Ocean is home to a collection of fascinating and famous plants and animals. They are fascinating due to the impressive amount of diversity they exhibit over such tiny distances and they are famous because of one of the men they fascinated. That man was named Charles Darwin and he visited the islands in the 1830s. Darwin’s observations on this journey were eventually synthesized in his famous book, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.

One group of birds is so associated with this trip (and Darwin’s subsequent visits to the islands) that they have become known as “Darwin’s finches”. Despite, their common name, these 14 species actually belong to the tanager family. Whatever their taxonomy, these birds live in a highly variable environment and have evolved an impressive array of beak shapes, behavioral patterns and feeding innovations to cope. A study conducted earlier this year indicates that Darwin’s finches are just as innovative in how they are coping with two relatively new introductions to their environment.

In 2012, Aron Cinadom and colleagues first observed finches doing something new. A warbler finch was seen tearing off leaves from a tree and rubbing them on its feathers. This was not an isolated incident. Over the next 4 years, they observed other species of Darwin’s finches applying leaves to their feathers. Intriguingly, while different bird species were doing the rubbing, they were all applying leaves from the same endemic tree, a Guayabillo tree, to their feathers.

The team hypothesized that the Darwin’s finches were applying Guayabillo leaves to their feathers to protect them from newly introduced insect pests. Adult mosquitoes feed on these birds and recent introductions of new mosquito species, and with them avian pox, have made mosquito bites a serious risk. In addition, a species of fly, Philornis downsi has been newly introduced. As adults they feed on fruit, but as larvae they reside in nest material and attack developing bird nestlings at night.

Birds in other habitats have been observed to rub themselves with ants, millipedes, gastropods, citrus, onions, resin and other vegetation. These rubbings have been found to have bactericidal and fungicidal properties as well as functioning as a deterrent or repellent for arthropod pests ranging from ticks to armyworms. Cinadom and colleagues set out to determine whether these newly observed behaviors where adaptation to cope with these new threats. Were the Darwin’s finches applying insect repellent? They have recently reported their findings.

A series of experiments on several mosquito species demonstrated that the leaves might be an effective mosquito repellent. A field experiment demonstrated that the leaves were good enough to repel mosquitoes from people. When local mosquito populations were offered volunteer arms that were or were not coated with crushed Guyabillo leaves, the mosquitoes were less likely to bite treated arms. In the lab, other mosquito species were less interested in taking bloodmeals from feeders treated in the same way. These results suggested that mosquitoes might be less inclined to bite a bird that had rubbed Guayabillo leaves on their feathers.

Both immature and adult P. downsi also has an adverse response to the leaves. P. downsi larvae had difficulty feeding on chicken blood when gauze treated with Gauyabillo leaves was used as a barrier. Similarly, y-tube experiments suggested that adult flies were repelled by the leaves. Further studies confirmed that P. downsi is able to detect several volatile compounds in the leaf extracts. These included several sesquiterpenes which function as herbivore deterrents in other plants.

Many questions remain here. It is unclear how much of the chemicals from the leaves end up in the bird feathers. The birds have been observed to use two methods to apply the leaves. Some thread the leaves through the feathers (the “sponge” method) and others chew the leaves and apply mashed leaves to the feathers (the “lotion method”). It is unknown what effective concentrations of plant volatiles are left on the feather by these methods. Interestingly, it does not appear that certain species use one strategy or the other to apply the leaves. Are some application methods better for certain pests?

There is potential that further investigation into what makes Guayabillo leaves repellent could lead to novel insect repellents. While the leaves contain chemicals which mosquitoes (shown in this study) and P. downsi (current study) respond to, it is unclear how repellent these chemicals are compared with something like DEET. Questions still linger about how the birds have evolved to utilize these particular leaves. The field of bird olfaction and cognition are just beginning to collide and there is evidence that birds can use chemical cues in other contexts.

Perhaps most immediately, the study demonstrates that Darwin’s finches are under threat. Like so many animals in so many places they are experiencing new challenges brought on largely by human activity. These birds have existed successfully on the Galapagos because they are highly adaptable. If we wish to conserve these fascinating species, we will need to come up with ways to help control the arthropod pests and the associated diseases we have unleashed on the islands.

Comments