Contact tracing for disease control

Syphilis and gonorrhea incidence have increased enormously in recent decades, necessitating innovative approaches. The rising prevalence of syphilis and gonorrhea, together with the increase in prevalence of resistant gonorrhea, makes contact tracing an important tool for disease control. In connection with the opioid epidemic, syphilis is now common in rural areas. However, people infected with stigmatized diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea may be reluctant to reveal all of their sexual contacts. Reasons for not revealing all contacts may include internalized stigma, cognitive dissonance, or beliefs that certain types of sexual contacts do not “count.”

Asking for friends might identify more sexually transmitted infection (STI) cases because friends may participate within the same sexual network, or some friends might be non-romantic sexual partners. One survey even found 77% of Grindr users report looking for friendship, more than the percentage seeking dating (67%), one-on-one sex (62%), or group sex (17%).[i]

Patients who were diagnosed with syphilis and gonorrhea in Baltimore City STI clinics were asked to name the most important people in their lives, with questions such as whom they eat meals with, who would take them to medical appointments, who would go to the store for them, or lend them $25. After patients named their friends and social contacts, they were asked to name their sexual contacts. Both social and sexual contacts were invited to the STI clinic for testing, and to name their own social and sexual contacts.

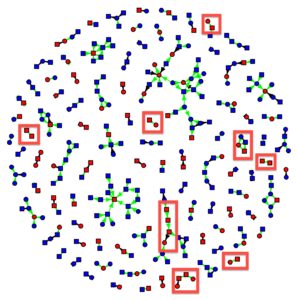

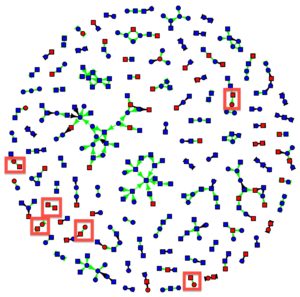

Using this information for patients whose contacts visited the STI clinic, we created a network showing the friendship and sexual contacts and the STI test results. We identified new cases of both syphilis and gonorrhea within each network.

In Figure 1, the network shows new cases of syphilis identified by asking for social contacts in the large red squares.The small squares are males, and circles are females. Shapes colored red are the participants who tested positive for syphilis. The green arrows are social network connections and the black are sexual network connections. Biological strain analysis for the organism that causes syphilis (T. pallidum) found that the disease strains matched across connected individuals, suggesting that individuals were connected within the same sexual network, although not necessarily directly: the friends may have had sex together or have a sex partner in common that does not appear in the graph. It’s remarkable here that for many pairs where both were infected with syphilis (syphilis-concordant dyads, for short), no sexual partners appear in the graph, and in a few cases both are male.

We did the same for gonorrhea. As before, new cases of gonorrhea identified by asking for social contacts are the large red squares. The small squares are males, and circles are females. Shapes colored red are the participants who tested positive for gonorrhea. The green arrows are social network connections and the black are sexual network connections.

The additional cases of syphilis and gonorrhea identified by asking friendship ties suggest that they under-reported their sexual contacts. These friendship ties may actually be sexual ties that were not reported as sexual; many of these ties were same-sex, and same-sex ties were stigmatized in this community, especially at the time that the data were collected (2001-05). Alternatively, these friendship ties may represent participation in the same sexual networks, such as engaging in a sexual relationship with the same person or people, who were not observed in the data.

Learning from COVID-19

Given existing strains on public health resources, public health policy must be creative. Traditionally, contact tracing is done by Disease Intervention Specialists. However, the 2008 recession resulted in large cuts to public health agencies that were never reversed. The Disease Intervention Specialists currently do not have enough resources even to contact all sexual contacts of index cases of syphilis and gonorrhea, so they prioritize vulnerable populations, such as pregnant women. Public health agencies simply do not have resources to contact the friends of index cases, and index cases may not cooperate anyhow.

However, large technology companies have created privacy-preserving innovations in SARS-coronavirus-2 contact tracing protocols that have been deployed in state health department contact tracing apps. These contact tracing protocols identify nearby phones using Bluetooth and approximate the distance and duration. Public health authorities create COVID-19 contact tracing apps using these protocols that can specify distance and time duration for potential coronavirus contacts. These protocols or health department apps could be extended to contact tracing for other diseases. Changing the parameters for distance and duration on public health contact tracing apps could identify potential sexual contacts, allowing these apps to be used for STI contact tracing. The transition to these COVID-19 contact tracing apps has been bumpy, with technological limitations, low uptake, and lack of public trust, especially in government. The Bluetooth distance detection doesn’t do well near shiny surfaces or in public transit buses or trains, and while that’s a large problem for COVID-19 contact tracing, it’s not a problem for STIs. As with many US problems, low public trust in government is the limiting factor for contact tracing, whether traditional or by app.

[i] Landovitz R, Tseng C, Weissman M, Haymer M, Mendenhall B, Rogers K, Shoptaw S. Epidemiology, sexual risk behavior, and HIV prevention practices of men who have sex with men using GRINDR in Los Angeles, California. J Urban Health. 2013; 90(4):729–739.

Comments