Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disease causing a build up of thick, viscous mucous in the airways, which makes CF patients highly susceptible to infections. The most common culprit is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a highly virulent opportunistic pathogen. These infections are associated with declining lung function, reduced quality of life and ultimately, premature death. To make matters worse, P. aeruginosa is now resistant to virtually all commonly administered antibiotics, making it seemingly impossible to eradicate once established.

P. aeruginosa rapidly adapts to life within the CF lung via a series of genetic and phenotypic changes, including, most strikingly, the loss of many secreted proteins and sugars which are linked to virulence. The loss of these traits in chronic infections has been observed time and time again, e.g. here and here, leading to the widely-held assumption that virulence is generally bad for the bugs in chronic infections.

Increasingly, however, CF infections worldwide are dominated by highly transmissible epidemic strains that must retain their virulence-associated traits in order to allow them to transmit to new hosts. This prompted us to question just how universal the assumed loss of virulence-associated traits really is in CF chronic infections.

A possible solution to this problem is that P. aeruginosa populations in the CF lung are not uniform, but highly diverse. Even by sampling just a few colonies we can see diversity in clinically important traits like antibiotic resistance (e.g. here and here). Perhaps diversity in virulence-associated traits might explain how virulence could be reduced overall in chronic infections while still maintaining the ability for some genotypes to infect new hosts?

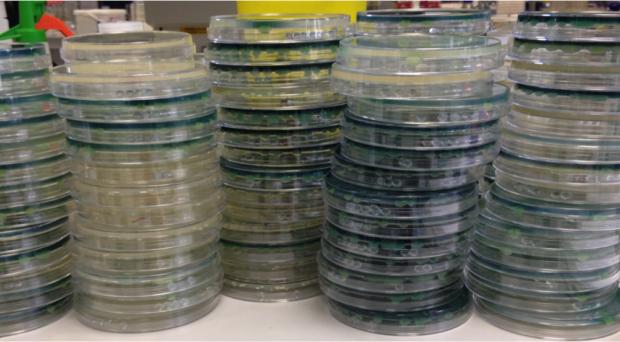

We set out to investigate this by quantifying phenotypic variation in P. aeruginosa isolates within the lungs of several CF patients. Our approach was different from previous studies – rather than sampling a few isolates from a large number of patients over time, we sampled 40 isolates from three samples taken from different CF patients (all at a similar stage of infection).

Our results revealed that in two out of three patients, the bacterial populations were highly diverse in their production of secreted peptides and proteins linked to virulence, ranging from non-producing genotypes to hyper-producers which had evolved to pump out these virulence-associated secretions at very high levels.

The question then was, does this variation actually matter for establishing virulent infections in a new host? We tested this in waxmoth larvae, by individually infecting single larvae with each of 40 isolates taken from a single patient sample. We found that isolates that produced higher levels of these secretions killed the waxmoths much faster than non-producing isolates, even though all of these isolates once coexisted together in the same lung.

Our work suggests that this diversity within the CF lung explains the ability of P. aeruginosa to transmit from patient to patient in CF clinics. In these CF infections, despite reduced virulence at the whole population level, the diversity means that there is a highly-virulent sub-population capable of causing new infections. What we don’t yet know is why the diversity evolves and how it is maintained for such long periods in the CF lung. Nonetheless, we have shown that within-patient P. aeruginosa diversity matters, suggesting that accounting for diversity is key to accurately diagnosing and treating CF infections.

Comments