An ancient finding

For 12,000 years they lay cradling one another. Their embrace shows that even at the dawn of civilization, we were not alone. Surely the puppy had a name – one that was called out, sometimes affectionately, sometimes sternly by the person whose ancient finger bones were found wrapped around it. Today such sounds are familiar. Back then they heralded the beginning of a partnership that would come to define both species.

Unearthed within a tomb of the prehistoric settlement of Ain Mallaha, in Northern Israel, these remains belonged to the Natufian culture. Their settlements provide evidence of a people transitioning from hunter-gathering to a way of life centered around domesticated plants and animals.

It appears that dogs were the first species to enter into the fold. Genetic evidence indicates that dog domestication started sometime between 11,000-16,000 years ago. These bones provide physical evidence from the early stages of this special relationship between human and dog.

The genetics of dog domestication

Before dogs could enter our homes they had to become tame. Yet there is much about the biology behind this transformation that we still don’t know.

Before dogs could enter our homes they had to become tame. Yet there is much about the biology behind this transformation that we still don’t know. To better understand why dogs bound up where wolves fear to tread we turned to the largest publicly available database of dog and wolf genomes.

From this database, called DoGSD, we compared the genomes of 69 dogs and 7 wolves. The animals were collected from several different locations around the globe.

We identified single nucleotide variants where dogs and wolves are highly differentiated.

Among these we found 2,112 single nucleotide positions in the genome where dogs and wolves completely differ. In other words, if you looked at any one of these sites, you could be sure whether the animal it came from was a dog or a wolf.

We suspected that some of these genetic differences underlie the physical and behavioral changes that occurred during dog domestication. To identify these functional changes we narrowed down our search by only considering the genetic changes that were predicted to change either the protein structure or amount of each gene that is produced.

What did we find?

We identified 848 genes with potentially functional genetic changes that differentiated the majority of dogs and wolves analyzed. To see what this might tell us about dog domestication we tested whether any specific biological pathways had more genes with high frequency genetic differences between dogs and wolves than you would expect by chance.

We found six biological pathways with a significant enrichment of genes with potentially functional differences between dogs and wolves.

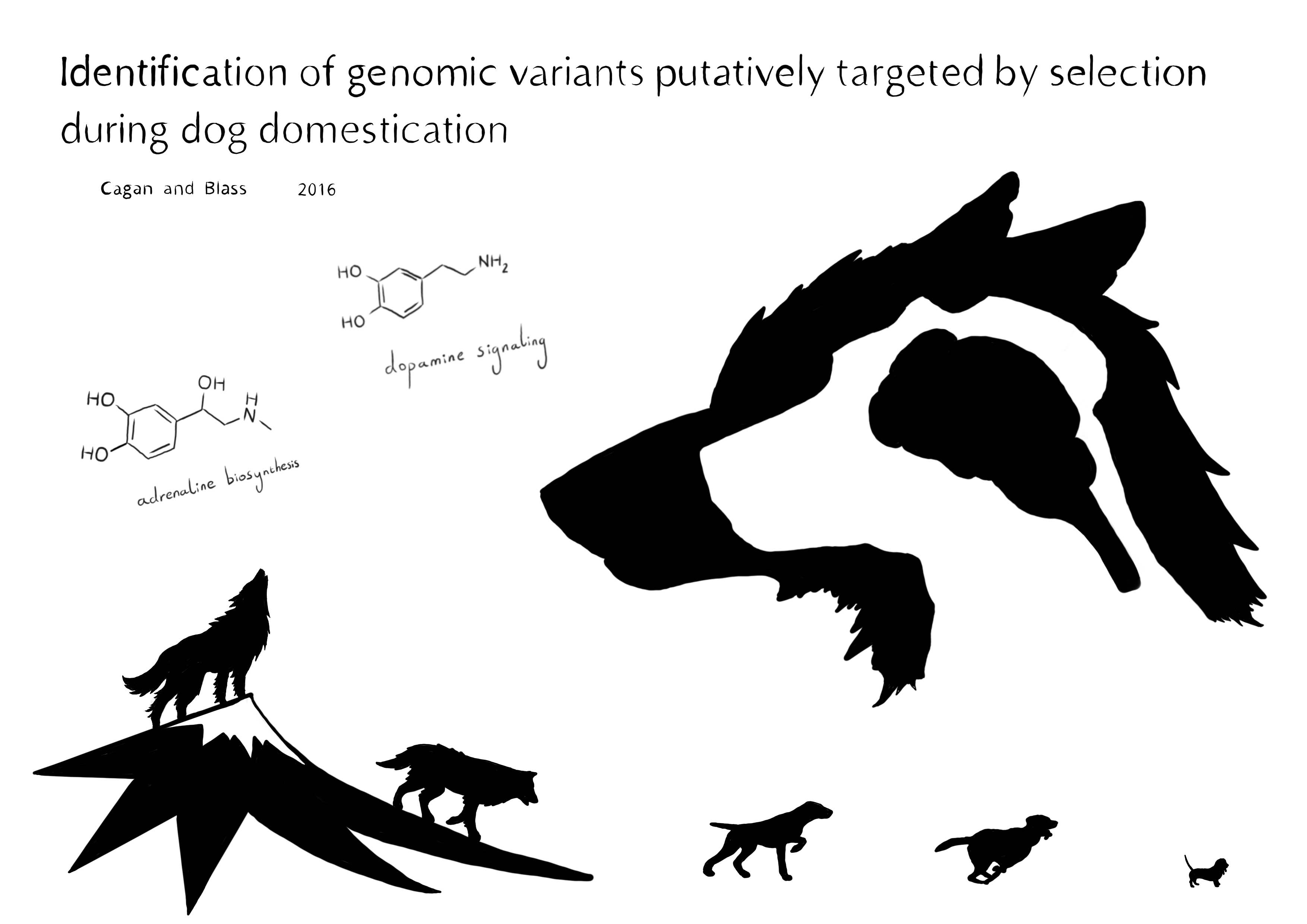

We found six biological pathways with a significant enrichment of genes with potentially functional differences between dogs and wolves. The strongest signal was in the adrenaline and noradrenaline biosynthesis pathway.

Adrenaline is a hormone with an important role in the fight-or-flight response. Therefore, we hypothesize that some of the genetic changes in this pathway may underlie the less fearful and aggressive behavior of dogs towards humans compared to wolves.

We also detected an enrichment of changes in genes in the dopamine signaling pathway. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter known for its involvement in emotional processing and reward behavior. We suspect that some of these changes were also important during dog domestication

What does this mean?

Interestingly, several of these genes contain other variants previously suggested to being associated with behavioral differences within or between dog breeds (for example SLC6A3 and MAOB). This suggests that these genes may have been important during both the initial domestication process and later breed formation.

These results highlight several genes with changes that may have been involved in the process of dog domestication. Future work will be needed to reveal exactly what effects, if any, these changes have. Furthermore, ancient DNA from dogs and wolves may tell us exactly when and where these changes occurred in the history of dog domestication.

Comments