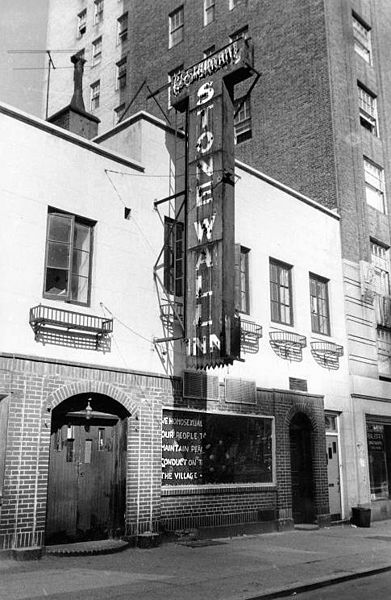

The Stonewall Riots occurred on June 28, 1969. It was this summer evening that sparked the Gay Rights Movement. Now, forty-eight years later, the world celebrates Pride Month every June to celebrate, honor, support, and fight for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) community.

The queer community is resilient. No matter what obstacles they encounter, their battle to live, pursue their passions, and contribute to society endures. For many queer people that passion is science. Queer scientists such as Alan Turing who was crucial in ending World War II, and Sara Josephine Baker who made unprecedented breakthroughs in child hygiene and preventative medicine.

This Blog post is meant to bring attention to queer scientists that are working in the field. Field research encompasses any type of scientific research that involves collecting data in non-laboratory locations. Several scientific areas involve field work such as zoology, paleontology, and botany. The field is a fun and exciting place to perform science, however for those who identify as queer1, working in the field can present challenges that may not be known to cis-gendered1 or straight scientists.

To be “in” or to be “out”? That is the question

The biggest decision for all LGBTQ individuals is whether to disclose their sexuality or gender identity. The decision to be out of the closet is an incredibly complex one in which all queer individuals have to evaluate the benefits versus costs. In general, staying in the closet and not disclosing one’s sexuality or gender identity can be incredibly caustic, but there are many situations where staying in the closet is potentially safer than being out.

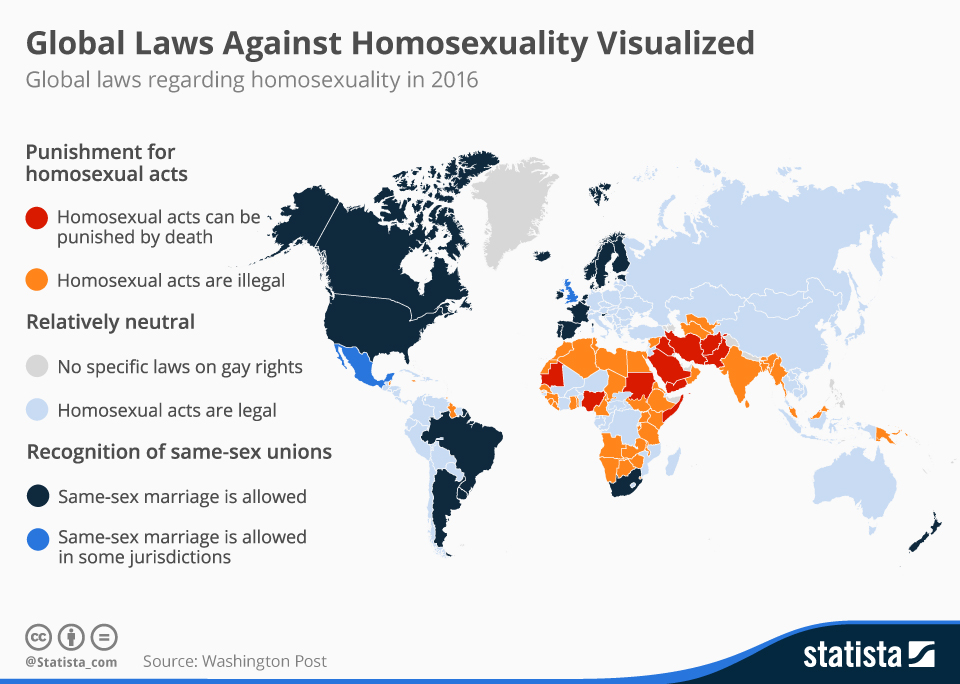

The risks for being out in the field are very location dependent. Dr. Siobhán Cooke from John’s Hopkins School of Medicine currently does work in the Dominican Republic and Colombia. She feels comfortable being out and talking about her wife while in the Dominican Republic and Columbia. However, when she did field work in Tanzania she did not come out because she thought it would be unsafe. African and Middle Eastern countries can be particularly dangerous for queer scientists. Homosexuality is punishable by death in Sudan, northern Nigeria, Somalia, and Saudi Arabia, and is illegal in a slew of other countries including Ethiopia, India, Tanzania and Uganda. These types of legal restrictions obviously make it unsafe for a queer scientist to be out.

Even if being LGBTQ is not illegal, local views and customs can make it unsafe or difficult for queer scientists to be out. Close relationships with locals are required for scientists to obtain permission to perform their research in a specific location or to garner an opportunity to employ locals to aid in data collection. Local stigma against queer people and the discovery that a queer scientist is in a research group can result in locals’ refusal to help the scientists.

Local stigma against queer people and the discovery that a queer scientist is in a research group can result in locals’ refusal to help the scientists.

Lewis Bartlett, a graduate student who studies bees in the United States’ South, has experienced these types of challenges. His research includes collaborations with rural beekeepers many of whom hold conservative views on LGBTQ individuals: “Parts of the fieldwork often involve extended social situations with collaborators, local practitioners etc. In these informal settings with food, drink, and an expectation to be charming and sociable it is absolutely a worry that you may say something which jeopardizes a rapport with a collaborator. Much of this kind of research – working with small hold beekeepers – is done on a very informal basis and requires maintaining strong personal connections with these people. It is absolutely distracting to have to police what directions conversations go in.”

Dr. Christopher Schmitt of Boston University explores mechanistic and adaptive aspects of developmental variation. While doing fieldwork in South Africa, it was relatively safe for Dr. Schmitt to be out. However, the potential for being out of the closet did not necessarily mean it was the best idea in terms of successfully carrying out his science. There was one experience where two of his local field workers were using homophobic epithets. Dr. Schmitt knew that it would be risky to express his disapproval or discomfort. Speaking up could have led the field workers to suspect he was gay thereby putting a strain on the working relationship and potentially impeding his research. Luckily in this situation, one of Dr. Schmitt’s colleagues to whom he was out did speak up to express their discomfort with how the field workers were talking.

The consequences of staying “in the closet”

Knowing that there are situations where it would be safer for queer scientists to stay in the closet while working in the field, a discussion on the deleterious consequences of staying in the closet is critical. Dr. John Pachankis from the Yale School of Public Health studies the psychological implications of staying in the closet. Through his research he has come up with a cognitive-affective-behavioral model of the consequences of staying in the closet. In this model Dr. Pachankis discusses the intersection between cognitive energy, affect, and behavior and its relationship to queer individuals remaining in the closet. Cognitive energy encompasses the amount of mental energy spent on psychological processes such as attention, reasoning, and decision making. Affect, meanwhile, describes emotional states such as joy, guilt, and depression.

In Dr. Pachankis’ description of his cognitive-affective-behavioral model, he explains how closeted individuals spend a significant amount of cognitive energy engaging in preoccupation and vigilance to make sure that others do not suspect they are queer. These cognitive activities of preoccupation and vigilance can result in affective responses of guilt, shame, demoralization and depression. These affective states, then have behavioral repercussions including avoiding social situations, weakening of close relationships, and engaging in risky behaviors such as unprotected sex and drug abuse.

While I never went ‘back in the closet’ (something I’m not sure I would know how to do anymore) it did undermine how authentically I felt I bonded with collaborators and colleagues.

Dr. Schmitt

Staying in the closet, therefore, puts unnecessary cognitive demands for a queer person in the field where their main goal is to be a good scientist and collect data. When Dr. Schmitt was doing research in Gambia he ended up leaving a month early. A large part of this was due to the strong anti-gay feelings in the country where the president of Gambia was putting stings on gay people and making comments about slitting the throats of gay people.

When going to field sites in conservative areas of the American South, Lewis Bartlett said “Being unaccustomed to ‘editing’ how I present makes consciously considering it always a shock (this fieldwork is an annual event) – modifying how I dress or act in order to not cause ‘unnecessary’ problems will always feel upsetting. While I never went ‘back in the closet’ (something I’m not sure I would know how to do anymore) it did undermine how authentically I felt I bonded with collaborators and colleagues.”

During an 18 month stint in Ecuador Dr. Schmitt described his experience of staying in closet. “I wasn’t ashamed of being gay, per se, but the same triggers that caused those feelings were there: having to hide, having to self-censor, playing the pronoun game, thinking twice before every statement, guarding your vocal inflections and hand gestures, choosing the correct interests to allay suspicions, making noncommittal comments about women when the other men ask for/expect them, getting crushes on men that you can’t think too much about or reveal or talk to anyone about or act on because it would cause problems… it’s all there again, and it’s all very hard to shake those feelings, even after years of living authentically and having grown into confidence as a gay adult”.

Unique challenges for Trans Scientists

Being transgendered in almost anywhere in the world is incredibly difficult, and this is of course true for transgender scientists working in the field, which presents its own unique challenges. Situations can be tricky for transgender scientists depending on where they are in their transitioning process. One challenge is documentation and paperwork. It can obviously be very problematic if the gender identification on all documentation is not the same. However, there can be even trickier situations.

One transgender scientist who had already been at a field site in East Africa prior to their physical transition knew that they were going to return to the field site. They made the very difficult decision of postponing their transition process. “I consider my decision to delay my physical transition in order to conduct fieldwork an incredible sacrifice. I would have to delay the start of my life for another year.” This postponement, however, was not sustainable, and they decided to start on a low dose of hormone replacement therapy. Although this decision was positive it was not without its challenges. “For me, this decision was life-saving and I am finally getting better and am able to enjoy my research as I did before. But it’s not an ideal situation. As I am becoming my authentic self, I have to carefully monitor how others are perceiving me. Has my voice dropped too much? Is my facial structure noticeable different?”

Advice for Principle Investigators and Academia

Discussing safety in relation to scientific research is standard. When going into the field, scientists are given a heads up on safety issues related to diseases and wildlife. They get vaccines, take anti-malarials, and take precautions on what water to drink. The amount of effort principle investigators put into preparing their students and field workers can vary. For some it is limited to basic preparation of what is expected of them in the field while others will determine if their students and field workers will be able to handle the psychological stressors of being in the field.

It could be beneficial for everyone if there was a standardized method to prepare individuals going into the field. In addition to principle investigators addressing disease risks and physical dangers, it would be valuable to talk about other potential safety issues such as cultural views related to queer people or women since dangers and safety issues are greater for these populations. By having these discussions standardized, it would mean that this information would be disseminated to scientists of all genders and sexualities. A standardized “script” would mean that principle investigator wouldn’t have to be worried about making assumptions of whether a prospective student or research assistant were queer. Furthermore, it is important for men, cis-gendered, and straight scientists to know the kinds of risks that their female and queer colleagues may encounter.

For Dr. Cooke who is in her first year being a principle investigator at an institution with graduate students, she plans on having these conversations since “carefully considered conversations about identity have generally not been on the table.” Furthermore, being out is especially important for Dr. Cooke “so that students know it is possible to be a queer woman scientist.”

1Terminology: Queer: an accepted umbrella term to describe individuals who are neither cis-gendered nor straight Cis-gendered: individuals whose gender identity matches with their biological sex

Disclaimer: All interviewees provided permission to use their names and quotes.

I think I see what you’re saying, but I don’t know if I understand, in which case maybe I don’t see what you’re saying.

What I don’t understand is why this is an issue? I can’t recall any time I discussed my sexuality or partners in field situations. It is not something I discuss or bring up and it doesn’t even occur to me this would be something I’d ask someone else.

I realize I’m a private person, but I don’t understand why anyone would feel pressure. It’s fairly easy to politely deflect personal inquiries, often with humour. Most people are good at recognizing personal boundaries and don’t transgress them in the first place.

But I suppose that is just me. As I said maybe I do see the point, but based on my experiences and my experiences alone I don’t think I understand. I’m aware of it now though so will pay attention in the future and perhaps I will understand one day.

In my experience I am asked frequently about my status–married or single, always with the presumption that I am looking for someone of the opposite sex (I am, but that is beside my point). When I say that I’m single they ask why, and then they ask don’t I want children. There aren’t personal boundaries–I’m asked any and all things. I’ve also been asked about the sexuality of my friends. It’s quite different than in the US where usually people don’t bring these things up. I don’t know if it’s the novelty of my situation (woman in 20s-40s (I’ve been working there a while), unmarried without children) or what, but those questions are never ending! When you work daily with a team and the questions come daily and you are trying to maintain both professional and personal relationships (you’re living and working with your team, after all), it’s not possible to deflect without feeling as if you are lying, censoring, or (I imagine) closeting yourself. I’m straight and it is difficult for me to constantly field questions with 100% honest answers, while also being culturally sensitive so as not to ruin my relationships, and not feeling exhausted by others asking about me as if I’m different in some way. These challenges are exacerbated and multiplied when you’re LGBTQ, and there are clearly some issues that most of us have never even thought about (e.g., delaying your transition). I thought the article was helpful for me as an educator and mentor of students who will go to the field, and as a colleague of LGBTQ field researchers, and I think that it will be especially helpful for those going to the field for the first time. These stories need to be told and shared so others recognize the issue, so that people know they aren’t alone, and so that strategies for dealing with these situations can be shared. At a minimum, the map can help one decide where not to do research.

For update, same-sex marriage is now legal in Colombia.

Awesome article! I really appreciate how you considered the unique needs of trans scientists. However, I do feel the need to point out that “being transgendered” should be “being transgender”. Like how you wouldn’t say “being gayed”. The -ed makes it sound like it’s something happening to you, instead of just a descriptor of who you are.